Noticing Space

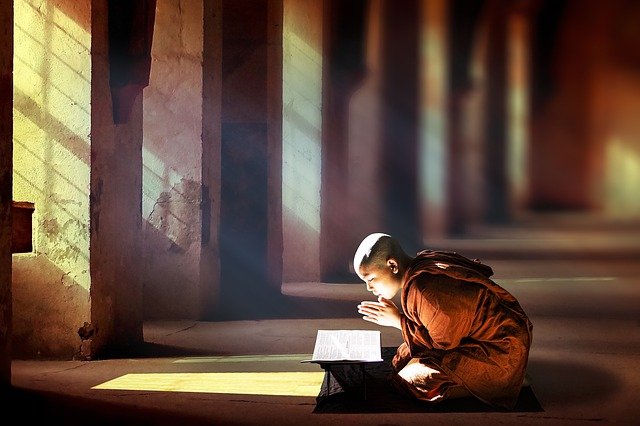

Acharn Sumedho

In meditation, we can be alert and attentive; it’s like listening – being with the moment as it is – just listening. What we are doing is bringing into awareness the way it is, noticing space and form – the Unconditioned and the Conditioned.

For example, we can notice the space in a room. Most people probably wouldn’t notice the space; they would notice the things in it – the people, the walls, the floor, the furniture. But in order to notice the space, what do you do? You withdraw your attention from the things, and bring your attention to the space. This does not mean getting rid of the things, or denying the things their right to be there. It merely means not concentrating on them, not going from one thing to another.

The space in a room is peaceful. The objects in the room can excite, repel, or attract, but the space has no quality that excites, repels, or attracts. But even though the space does not attract our attention, we can be fully aware of it, and we become aware of it when we are no longer absorbing into the objects in the room. When we reflect on the space in the room, we feel a sense of calm, because all space is the same; the space around you and the space around me are no different. It is not mine; I can’t say, “This space belongs to me” or “This space belongs to you.”

Space is always present. It makes it possible for us to be together, contained within a room, in a space that is limited by walls; but it is also outside the room. Space contains the whole building, the whole world. So space is not bound by objects in any way; it is not bound by anything. If we wish, we can view space as limited in a room, but really space is unlimited.

Spacious Mind

Noticing the space around people and things provides a different way of looking at them, and developing this spacious view is a way of opening oneself. When one has a spacious mind, there is room for everything. When one has a narrow mind, there is room for only a few things. Everything has to be manipulated and controlled, so that you have only what you think is right – what you want there – and everything else has to be pushed out.

Life with a narrow view is suppressed and constricted; it is always struggle. There is always tension involved in it, because it takes an enormous amount of energy to keep everything in order all the time. If you have a narrow view of life, the disorder of life has to be ordered for you; so you are always busy, manipulating the mind and rejecting things or holding on to them. This is the dukkha of ignorance, which comes from not understanding the way it is.

The spacious mind has room for everything. It is like the space in a room, which is never harmed by what goes in and out of it. In fact, we say “the space is in this room,” but actually the room is in the space – the whole building is in the space. Looking at it one way, the walls limit the space in the room. But looking at it another way, we see that space is limitless.

Space is something that you tend not to notice, because it doesn’t grasp your attention. It is not like a beautiful flower or a terrible disaster; it is something really beautiful or something really horrible that pulls your attention right to it. You can be mesmerized in an instant by something exciting, fascinating, horrible, or terrible; but you can’t do that with space, can you? To notice space you have to calm down; you have to contemplate it. This is because spaciousness has no extreme qualities; it is just spacious.

Flowers can be extremely beautiful, with bright reds and oranges and purples, with beautiful shapes that are dazzling to our minds. Something else, like garbage, can be ugly and disgusting. It’s not very noticeable and yet, without space, there would be nothing else. We wouldn’t be able to see anything else.

If you filled a room with things so that it became solid, or filled it up with cement, there would be no space left in the room. Then, of course, you couldn’t have beautiful flowers or anything else; it would just be a big block. It would be useless, wouldn’t it? So we need both; we need to appreciate form and space. They are the perfect couple, the true marriage, the perfect harmony – space and form. We can contemplate space and form and, from the broad perspective that develops, comes wisdom.

The Sound of Silence

We can apply this perspective to the mind, using the “I” consciousness to see space as an object. In the mind, we can see that there are the thoughts and emotions – the mental conditions – that arise and cease. Usually we are dazzled, repelled, or bound by these thoughts and emotions. We go from one thing to another reacting, controlling, manipulating, or trying to get rid of them. So we never have any perspective in our lives. We become obsessed with either repression or indulgence of these mental conditions; we are caught in those two extremes.

With meditation, we have the opportunity to contemplate the mind. The silence of the mind is like the space in the room. It is always there, but it is subtle – it doesn’t stand out. It has no extreme quality that would stimulate and grasp our attention, so we have to be attentive in order to notice it. One way to focus attention on the silence of the mind is to notice the sound of silence.

One can use the sound of silence (the primordial sound, the sound of the mind, or whatever you want to call it) very skillfully, by bringing it up and paying attention to it. It has a high pitch that is quite difficult to describe. Even if you plug your ears, put your fingers against your ears, or are under water, you can hear it. It is a background sound that is not dependant upon the ears. We know it is independent because we hear this high pitched, vibrating sound even when the ears are blocked.

By concentrating your attention on the sound of silence for a while, you really begin to know it. You develop a mode of knowing in which you can reflect. It’s not a concentrated state you absorb into; it’s not a suppressive kind of concentrating. The mind is concentrated in a state of balance and openness, rather than absorbed into an object. One can use that balanced and open concentration as a way of seeing things in perspective, a way of letting things go.

Now I really want you to investigate this mode of knowing, so that you begin to see how to let go of things, rather than just having the idea that you should let go of things. You might come away from the Buddhist teachings with the idea that you should let go of things. Then, when you find that you can’t do it very easily, you might think, “Oh no, I can’t let go of things!” This type of judgment is another ego problem that you can create: “Only others can let go, but I can’t let go. I should let go, because Venerable Sumedho said everybody should let go.” That judgment manifestation of “I am,” isn’t it? And it is just a thought – a mental condition that exists temporarily within the spaciousness of the mind.

Space around Thoughts

Take that simple sentence, “I am,” and begin to notice, contemplate, and reflect on the space around those two words. Rather than looking for something else, sustain attention on the space around the words. Look at thinking itself, really examining and investigating it. Now you can’t watch yourself habitually thinking, because as soon as you notice that you’re thinking, the thinking stops. You might be going along worrying, “I wonder if this will happen. What if that happens … mumble, mumble. Oh, I’m thinking,” and it stops.

To examine the thinking process, deliberately think something: take just one ordinary thought like “I am a human being,” and just look at it. If you look at the beginning of it, you can see that just before you say, “I,” there is a kind of empty space. Then, if you think in your mind, “I – am – a – human – being,” you will see space between the words. We are not looking at thought to see whether we have intelligent thoughts or stupid ones. Instead, we are deliberately thinking in order to notice the space around each thought. This way, we begin to have a perspective on the impermanent nature of thinking.

This is just a way of investigating, so that we can notice the emptiness when there is no thought in the mind. Try to focus on that space; see if you can concentrate on that space before and after a thought. For how long can you do it? Think, “I am a human being,” and just before you start thinking it, stay in that space just before you say it. Now that’s mindfulness isn’t it? Your mind is empty but there is also an intention to think a particular thought. Then think it; and at the end of the thought, try to stay in the space at the end. Does your mind stay empty?

Most of our suffering comes from habitual thinking. If we try to stop it out of aversion to thinking, we can’t; we just go on and on and on. So the important thing is not to get rid of thought, but to understand it. And we do this by concentrating on the space in the mind, rather than on the thoughts.

Our minds tend to get caught up with thoughts of attraction or aversion to objects, but the space around those thoughts is not attractive or repulsive. The space around an attractive thought and the space around a repulsive thought is not different, is it? Concentrating on the space between thoughts, we become less caught up in our preferences concerning the thoughts. So if you find that an obsessive thought of guilt, self-pity, or passion keeps coming up, then work with it in this way – deliberately think it, really bring it up as a conscious state, and notice the space around it.

It’s like looking at the space in a room: you don’t go looking for the space, do you? You are simply open to it, because it is here all the time. It is not anything you are going to find in the cupboard or in the next room. Or under the floor – it is right here now. So you open to its presence; you begin to notice that it is here.

If you are still concentrated on the curtains or the windows or the people, you don’t notice the space. But you don’t have to get rid of all those things to notice the space. Instead, you just open to the space; you notice it. Rather than focusing your attention on one thing, you are opening the mind completely. You are not choosing a conditioned object, but rather you are aware of the space in which the conditioned objects exist.

The Position of Buddha-Knowing

With the mind, you can apply inwardly the same open attention. When your eyes are closed, you can listen to the inner voices that go on in the mind. They say,” I am this… I should not be like that.” You can use those voices for taking you to the space between thoughts.

Rather than making a big problem about the obsessions and fears that go on in the mind, you can open your attention and see those obsessions and fears as mental conditions that come and go in space. This way, even an evil thought can take you to emptiness.

This way of knowing is very skillful, because it ends the mental battle in which you were trying to get rid of evil thoughts. You can give the devil his due. You now know that the devil is an impermanent thing. It arises and ceases in the mind, so you don’t have to make anything out of it. Devil or angels – they are all the same. Before, you’d have an evil thought and start creating a problem: “The devil’s after me. I’ve got to get rid of the devil!” Now, whether it’s getting rid of the devil, or grabbing hold of the angels, it is all dukkha. If you take up this cool position of Buddha-knowing – knowing the way things are – then everything becomes Dhamma. Everything becomes truth of the way it is. You see that all mental conditions arise and cease – the good along with the bad, the skilful along with the unskillful.

This is what we mean by reflection – beginning to notice the way it is. Rather than assuming that it should be any way at all, you are simply noticing. My purpose is not to tell you how it is, but to encourage you to notice for yourself. Don’t go around saying,”Venerable Sumedho told us the way it is.” I am not trying to present a way for you to consider, a way of reflecting on your own experience, a way of knowing your own mind.

Question: Some people talk about Jhanas, states of absorption, in Buddhist meditation. What are they, and how do they fit in with mindfulness, insight and reflection?

Answer: The Jhanas help you develop the mind. Each Jhana is a refinement of consciousness and, as a group, they teach you to concentrate your attention on increasingly refined objects. Through mindfulness and reflection, not willfulness, you become very aware of the quality and the result of what you’re doing. When you practice one Jhana after the other, you develop the ability to sustain attention on objects that are more and more refined. You develop great skill in this practice and you experience the bliss that comes from absorbing into increasing refinements of consciousness.

The Buddha recommended Jhana practice as a skillful means, but not as an end in itself. If you let it become an end in itself, you become attached to refinement and you suffer, because so much of our human existence is not refined but quite course.

In contrast to Jhana practice, the vipassana meditations (insight meditations) focus on the way things are, the impermanence of conditions, and the suffering that comes from attachments. Vipassana meditations teach us that the way about of suffering is not through refinements in consciousness, but through non-grasping of anything at all – not even the desire for absorption in any level of consciousness.

Question: So insight is reflecting on the grasping mind?

Answer: Yes, insight always notices the result of grasping and develops Right Understanding. For example, contemplation on the Four Noble Truths allows us to have Right Understanding, so that self-view and self-conceit are penetrated with wisdom. When there is Right Understanding, we are not practicing Jhanas from selfish intention; they represent a skillful way to cultivate the mind, rather than an attempt at personal attainment. People get it wrong when they approach meditation with the idea of attainment and achievement. That always comes from basic problem of ignorance and self-view, combined with desire and clinging. And it always creates suffering.